|

Local Clubs Albany Corvallis Dallas McMinnville Salem Springfield News & Information Meeting Times & Locations Special Events Club Newsletters Articles Home Home |

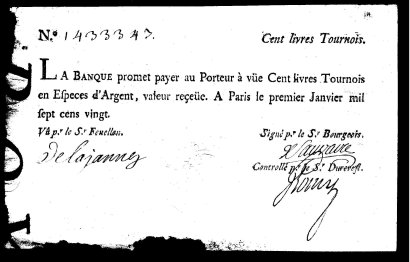

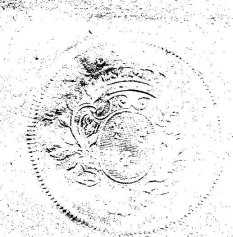

Mississippi Bubble.comGreg Franck-Weiby Note: Click on any image to view a larger version. The subject of this program is the oldest banknote in my collection and the newest stock certificate in my collection. The oldest banknote is a note for one hundred livre tournois of the Banque Royale of France dated January first 1720. This is what is known as a 'John Law note'. The newest stock certificate is one share of Enron, dated April 11, 2002. The connection between these two pieces of paper is the story of how dreams of unimaginably vast wealth have lead to financial disasters. First, the numismatic observations: The first European government sanctioned paper money was issued in Sweden in the 1660's, but most historians regard the Swedish notes as an unsuccessful issue. The first successful issue was by the Bank of England in 1694 (with the first printed notes issued in 1695), so this Banque Royal note is only a quarter century newer than the 'first' paper money. Since all Bank of England notes before the 20th century are scarce to rare, these 'John Law notes' are about the oldest collectible notes available. The Banque Royale note is rather plain looking, printed by letter press with three handwritten signatures and a handwritten serial number all in sepia ink. It is printed on watermarked paper (although watermarks were a great novelty for Americans starting with the 1996 series Federal Reserve notes, in fact watermarks have been used on paper money from the beginning). In this case, the watermark is just a line of lettering. The most attractive feature of this note is an embossed seal inscribed "Banque Royale" with the French Royal coat of arms, made with embossing dies of comparable quality to the contemporary coining dies.  So how much was a hundred livre tournois? The word 'livre' is just French for 'pound', and in the early middle ages that meant a pound of silver, minted into 240 deniers (or 'pennies' in English). ('Tournois' meant the weight standard of the City of Tours.) French money suffered inflation throughout its history, so 'livre' came to mean 240 deniers regardless of how much that many coins weighed, and that soon came to be much less than a pound. By the mid 17th century, a silver ecu, a crown sized coin weighing nearly an ounce, was valued at three livres. The coin illustrated, dated 1720, Paris Mint, is a one third ecu. In the 1680's that was equal to one livre tournois.

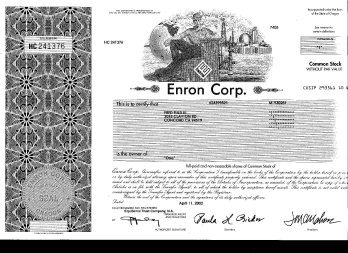

What appear to be lines across the portrait are the remnants of the coin's original design of paired L's (for Louis). The French used old coins as blanks to strike new coins of the same silver content, but with a different design to indicate a raised face value. By 1720, one third ecu was valued at one and one third livre tournois, so the hundred livres note was equivalent to 75 of these coins, or 25 silver ecus (equivalent to about thirty silver dollars). For comparison, the first U.S. census in 1790 showed Americans' per capita income was about a hundred silver dollars, so a hundred livres was a substantial amount of money in the 18th century. The reason the French had to revalue their coins in the late 1600's and early 1700's was the expense of fighting many wars. Louis XIV was King of France for 72 years, and the last quarter century of his reign was taken up with practically continuous wars of expansion as he pursued the goal of making France the most powerful state in Europe. France's enemies, including the Holy Roman Empire (the Austrians), the Dutch and the British, were forced to spend vast amounts of money in attempts to contain France, threatening those countries with financial crisis. In 1694, a Scotsman named William Paterson came up with a brilliant solution; he proposed the creation of the Bank of England. The way it worked was that the Bank of England was a privately owned bank chartered by Parliament. There was a time lag between the Crown collecting taxes and spending the money. During that interval, the government deposited its tax receipts in the Bank of England, which in turn loaned the money out at interest. The most profitable enterprise to invest in was the East India Company. It was also a very safe investment because of the maritime insurance provided by the underwriters who met at Lloyd's Coffee House in London (which, of course, became the biggest insurance brokerage in the world as Lloyd's of London). The India company was able to repay the loans with interest, enabling the Bank of England to pay dividends to its shareholders and interest to the government on the deposited taxes, enabling the government to spend more money than it collected in taxes without running a deficit. It was a Republican dream. (It was also no coincidence that the members of Parliament who chartered the Bank of England also bought shares in the Bank and happened to be leading investors in the India Co. The money goes 'round and 'round - and comes out here ;-) Louis XIV's last big war was the War of the Spanish Succession (known in the British North American colonies as 'Queen Anne's War') from 1702 to 1713. At the time, France had the largest, best equipped, best organized army in Europe. Yet despite that they were repeatedly beaten by the British under the command of the brilliant general, Lord John Churchill, the Duke of Marlborough (incidently, the direct ancestor of the WWII Prime Minister Winston Churchill). The British won all of the battles, but lost the war. They lost by default because Parliament got tired of paying for it and cut the funding for the military. Louis XIV won the war at the expense of bankrupting France. The timing was particularly significant because both France and England were poised on the threshhold of the Industrial Revolution. France was larger than England, had comparable natural and human resources, and comparable science and technology (e.g. the first working steamboat was designed by a Frenchman in the 1680's, but the first commercially successful steamboat was built in Scotland in 1804). At the critical moment in history, France didn't have the financial structure to be able to exploit the opportunities, and England did, enabling Britain to stay one step ahead of France throughout the Industrial Revolution and right up through WWII. Louis XIV outlived his son and grandson, so when he died in 1715, he was succeeded by a great- grandson who was still a child. The Regent for the young Louis XV, the Duke of Orleans, was faced with a financial crisis. At that point, John Law entered the picture. John Law was an interesting character. A Scotsman and the son of a goldsmith (by issuing deposit receipts that circulated as a proto-paper money, goldsmiths became the bankers of the 17th century), he was a brilliant mathematician. He was also a gambler and what is euphemistically called a 'lady's man' - and that's what got him into trouble. He killed a Mr. Wilson in a duel, presumably over the alienated affections of Mrs. Wilson; John Law was convicted of murder and sentenced to hang. However, he purchased a commutation of his sentence and fled to the Continent. Shortly after his old gambling buddy, the Duke of Orleans, became Regent of France, John Law showed up to tell him, 'I have the solution to all of your problems'. John Law proposed the establishment of the French equivalent of the Bank of England. In 1716 he set up the Banqe Generale and started issuing paper money. Two years later, Law's bank was reorganized as the Banque Royale, which issued this note. France had an East India Company, but it was nowhere nearly as successful as the Honorable East India Company in England, so John Law organized the Companie de l'Occident (the Company of the West) in order to develope the Louisiana territory. (By the way, last week was the two hundredth anniversary of Thomas Jefferson's purchase of the Louisiana Territory from the French.) Le Companie de l'Occident was more commonly known as the Mississippi Company. The foundation of John Law's financial empire was that he loaned paper money to investors to buy shares of the Mississippi Company. His 'IPO' was relatively small, but for his second issue of stock, he required that investors hold a certain percentage of their portfolio in shares of the first issue. That drove up the price of the first issue stock in the secondary market, guaranteeing that the early investors would make a quick profit in what developed into a 'pyramid scheme'. As the early investors started making a lot of money just by buying and selling paper, an increasing number of people wanted to get in on the action. Stock prices doubled in as little as forty days. In less than four years, the value of the stock increased fifty-fold. Law used a combination of government influence and clever promotion. For example, he hired unemployed men to dress as miners and march through the streets of Paris carrying picks and shovels to give the impression that they were on their way to Louisiana to dig up tons of gold and silver. The Mississippi Company founded a new city in Lousiana and named it after Law's patron, the Duke of Orleans - i.e. the City of New Orleans. The Regent returned the favor by making John Law the Duke of Arkansas (that might not sound impressive now, but at the time, nobody really had any idea of what was there - or not). John Law was given control of the French tobacco monopoly, and a monopoly on all of the trade with French Canada. The economic power of the Mississippi Company was further magnified by its merger with the French India company and the French China company. Eventually he was made Comptroller General of France, responsible for all tax collections, and the Director of the French mints, with the power to revalue French coinage. In March of 1720 he actually decreed that gold and silver coinage was no longer legal tender - debts had to be paid using notes of the Banque Royale, meaning that anybody with substantial quantities of gold or silver had to deposit it in his bank. This whole new financial system Law created was immensely successful. So many people got so rich so fast that the word 'millionaire' had to be invented. These nouveaux riche spent their new wealth freely on fine homes, furniture, clothing and big parties. That stimulated production and created employment for all classes. The economy of France boomed. That created an investment frenzy. The stocks could only be purchased in Paris, so 30,000 people converged on the city to invest. Stage coaches to Paris were booked months in advance. People who weren't able to get a seat on a stagecoach invested in future stagecoach tickets - and got rich doing that. There were skeptics who wondered where all of this wealth was coming from. There were only about a thousand Frenchmen in the whole vast Louisiana Territory, and most of them were soldiers, convicts, or prostitutes. The skeptics noted that there weren't actually any ships arriving from Louisisana unloading tons of gold and silver, or much of anything. Everybody else said, 'well, we don't actually understand how it works, but who cares? We're getting rich!'. However, in late 1719, trouble began to emerge. A few investors got overextended and had to dump their stock. The share prices stopped going up. Once that happened, the most savvy investors decided it was time to divest. The prices started going down. In the first eight months of 1720, the whole pyramid collapsed - 'the Mississippi Bubble' burst - and John Law had to run for his life! He wound up dying in poverty in Italy nine years later. The Banque Royale had issued paper money valued at twice the total of all the gold and silver coinage in France. By the time the value of the coinage stabilized in 1726, that one third ecu coin was worth two livre tournois. In the fall of 1720, a great bonfire was made in a public square where all of the remaining Banque Royale notes and shares of the Mississippi Company were burned. France didn't issue any more paper money for more than fifty years. Meanwhile the Bank of England continued to issue banknotes of stable value while the Industrial Revolution began in earnest. Perhaps that is why we Americans speak English instead of French. So, what does the Mississippi Bubble have to do with Enron and the 'dot-com' bubble that burst in recent years? The 'dot-com' bubble was the same kind of investment frenzy as the Mississippi Company bubble, where people got rich trading in stocks of high tech start up companies that had no products and no profits - only an idea that might be very profitable in the future. Enron was not only the biggest company to go bankrupt in that investment market, but there were also remarkable parallels between John Law's financial empire and that of Enron CEO Ken Lay. Both used political influence at the highest levels, both used deceptive promotion tactics, and both created networks of inter-related companies to make their scheme work. As for political influence, Ken Lay and Enron together donated over a million dollars to George Bush's political campaigns. Bush campaigned for President in an Enron corporate jet. In return, officers of Enron got to write the Bush administration's energy policies and approve the appointment of federal regulators overseeing their own industry. Fifty-two officers and employees of Enron wound up holding high offices in the Bush administration. As for deceptive promotion tactics, like Law's 'miners' marching through Paris, one Enron employee reported that when investors visited Enron corporate headquarters in Houston, they were lead through whole floors of offices where temporary employees were hired to sit at desks and look busy, although they didn't actually have any work to do. Enron created 3,000 other companies as subsidiaries and 'partnerships' in order to conceal the corporation's debts in order to lead analysts to over value Enron's stock based on mis-represented debt to equity ratios. Enron was able to purchase enough other actual energy producers that it came to dominate the energy market. When, for example, California utilities then approached Enron to negotiate long term delivery contracts, Enron showed them contracts with other companies at grossly inflated prices. The utilities didn't realize that they were competing against companies that were actually part of Enron. As a result, a friend of mine who lives in Eureka, California, saw his electric bill go from under a hundred dollars a month to nearly $800 a month (- talk about an 'electric shock'!) . The most interesting thing about my Enron stock certificate is that it bears the Oregon Corporate Seal of Enron. That could be because the only real tangible asset Enron held when it collapsed is Portland General Electric - the utility I pay my electric bill to. We still don't know if Enron will keep it, sell it to another company, or to the City of Portland or to a Public Utility District. Probably the most significant similarity between John Law and Ken Lay is that they both succeeded in persuading people that they had somehow re-invented the laws of economics. Law described it as 'the true philosopher's stone' - something that can transmute lead into gold - or in his case, paper into gold. Enron employees enthusiastically explained Enron's unbelievable profits by claiming that it represented a whole new way of doing business. The truth is that there was nothing new about it at all. It had all happened 282 years earlier with similarly disastrous results. So what was Ken Lay thinking? Maybe he thought that he could make it work when John Law couldn't because now we have computers to tweak the system. Maybe he knew it was a pyramid scheme that would inevitably fail, but that, unlike John Law, he could tell when to get out ahead of the collapse. Arguably Lay was more successful than Law; Law had to flee into exile and he died in poverty, while Lay is still a millionaire, and he'll probably never even be prosecuted. On the other hand, Law may have been a gambler convicted of homicide, but I haven't read that he did anything as sleazy as Lay telling his own employees to buy Enron stock at the same time he was dumping his own stock. So, what is one share of Enron worth? At the end of 2000, Enron shares peaked at $84.87 per share. Eleven months later they were worth less than one dollar a share. The fact that this share certificate is dated five months later probably indicates that somebody purchased some nearly worthless shares in order to generate the stock certificates for collectors to buy for far more than the stock is actually worth. However, if we could learn the lesson of history from this certificate, its value would be priceless.  Got an article you'd like to submit? Send it to info@oregoncoinclubs.org. |